Is There a Connection Between Hurricanes and Red Tide, and does a Warming Climate Play a Role?

The title background image shows Florida’s “red tide”, Karenia brevis, along the Gulf coast. (Image credit: P. Schmidt, Charlotte Sun)

2020 was a banner year for tropical storms with the just ended season yielding a record 30 named storms! We will soon post a new article on this historic hurricane season.

I am often asked if hurricanes have an impact on Red Tide and other algae blooms and is climate change playing a role? The answer to both questions is YES.

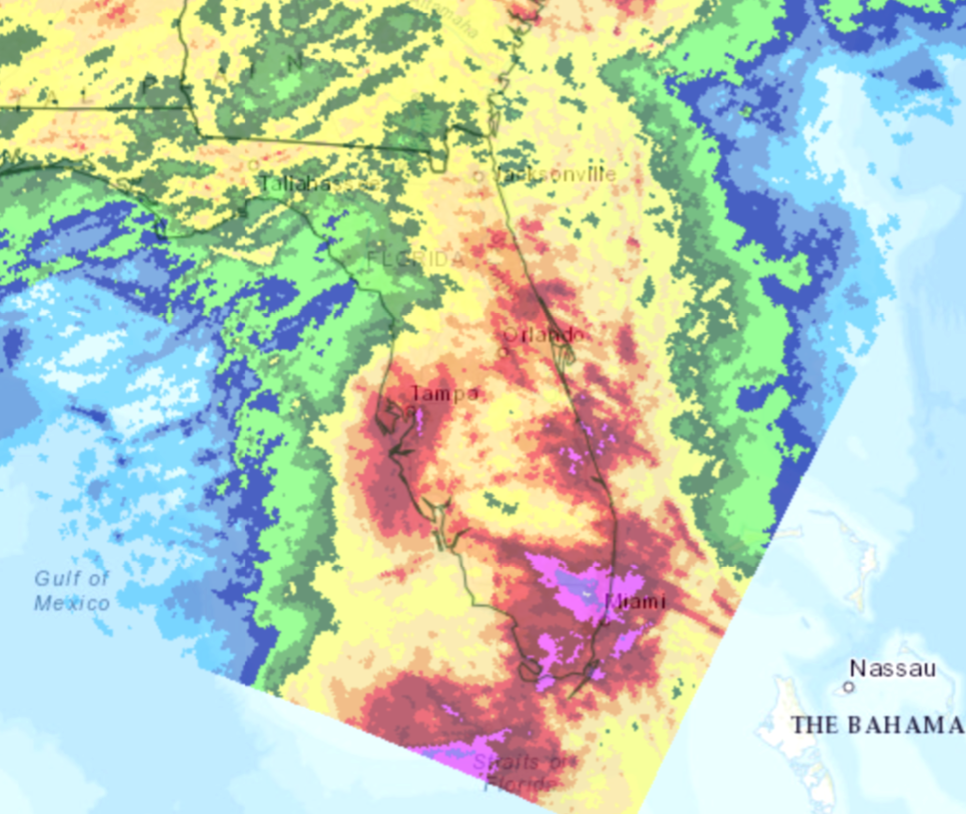

Southwest Florida was fortunate to have only two of the 30 named tropical storms in 2020, including the late-season strike of tropical storm Eta on November 12th. As the storm crossed Cuba after ravaging Central America as a strong Category 4 storm, it began soaking the southern two thirds of Florida with the heaviest rains of the hurricane season. During a 3-day period, many locations were drenched with 5 to 15 inches of rain as shown in this November composite of precipitation accumulations.

The red areas shown above, are rainfall accumulations of about 7 inches while the purple areas indicate 12 inches or more.

What does this have to do with Red Tide? Over the years I’ve observed many summer season heavy rainfall events. The runoff from heavy rainfall events like this one flushes the Florida landmass en route to the Gulf of Mexico.

That runoff contains rich nutrients from overflowing storm water systems, more than a million septic systems, massive agricultural operations and drainage from golf courses, yards, farms, etc. Upon flowing into the Gulf these nutrients act as fertilizer for Karenia brevis (Kb), commonly called Red Tide. About two weeks after a big flush, monitoring stations begin measuring higher counts of this Red Tide as these single celled photosynthetic organisms experience a population explosion.

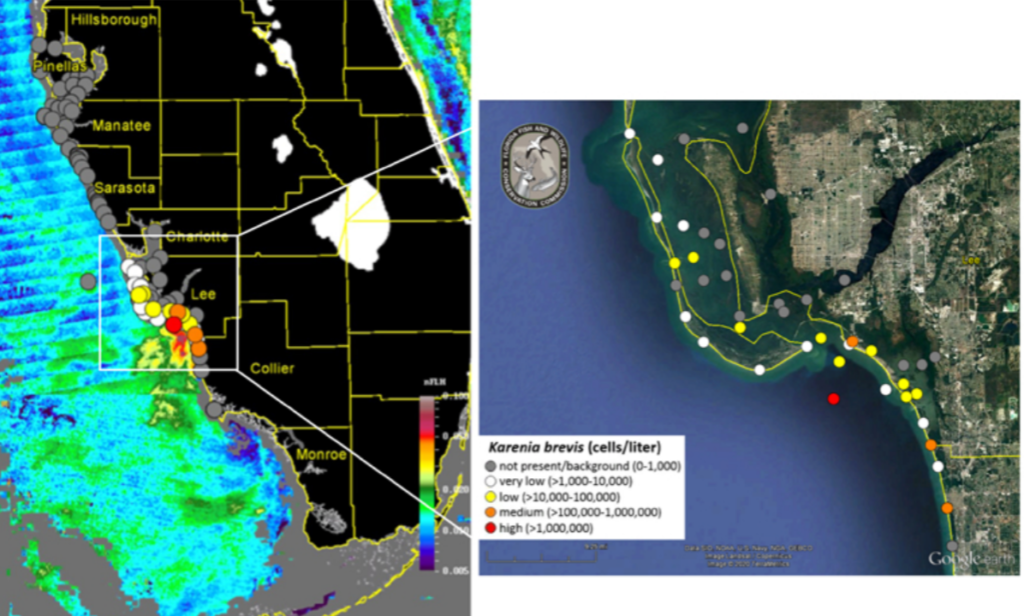

This image below shows Kb measurements from December 3rd to 10th, just three weeks after the passage of Tropical Storm Eta. Note the clustering of yellow and red dots on the southwest Florida coast not far from the major drainages from central and south Florida that empty into the Gulf around Charlotte Bay.

Karenia brevis measurements, December 3-10, 2020. Image credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

Hurricanes, when they create massive runoff events, are key to setting off Red Tides in Southwest Florida. Rising sea surface temperatures are rocket fuel for tropical storms and with record sea surface temperatures these past few hurricane seasons the number and severity of storms has been very high.

The more tropical systems that form the greater the chances of having major rainfall episodes driving nitrogen rich runoff into the Gulf, triggering Red Tide events 2 to 3 weeks later. It’s a toxic combination! The neurotoxins released by Red Tides threaten the health of fish, wildlife and humans and can create significant economic damage to areas where it occurs.

One other important climate warming effect enhancing Red Tide is the rise of winter ocean temperatures in the Gulf of Mexico. In the past, water temperatures in the Gulf cool below 60°F – a critical Kb temperature limit – for a time each winter. In recent years however the Gulf has sometimes remained warmer than this critical temperature.

When the Gulf water temperature drops below 60°F, Kb dies back strongly, but when it stays above that critical level the Kb survives in greater concentrations. That means Kb has a head start the next season as it multiplies from a higher starting baseline. In such years, if a hurricane provides a major widespread runoff event, the Kb can multiply explosively and cause major Red Tide outbreaks like the ones we experienced in late 2017 though early 2019.

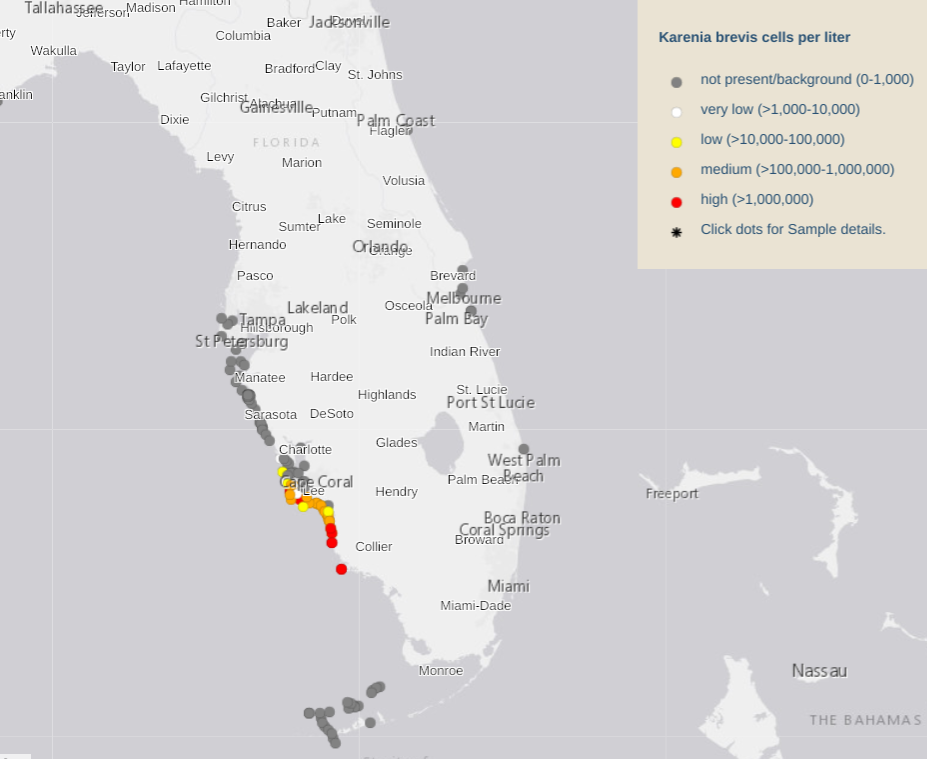

Thankfully 2020’s flush was late in the year and cooler water temperatures in December have prevented a wide-area outbreak of Red Tide from developing. Here are the outbreak locations as of January 8, 2021. Since early December the severity of the Red Tide has increased as it’s drifted slowly south, driven by northerly winds.

Kb sample data as of January 8, 2021. Image credit: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

But with a warmer than average winter expected this year, Kb may be waiting for next year’s tropical storms, which most often occur from July – September, as a triggering event. Is there anything we can do about Red Tides? Stay tuned for more insights coming from the Climate Adaptation Center in future newsletters and website articles.