Why Laura’s rapid intensification worries scientists

Scientists say warmer seas due to climate change are causing hurricanes to suddenly grow in strength. Are Laura, Michael, and Harvey a sign of the times?

Author: David C Adams (Originally published by Univision News, August 29, 2020. Reprinted with permission of the author.)

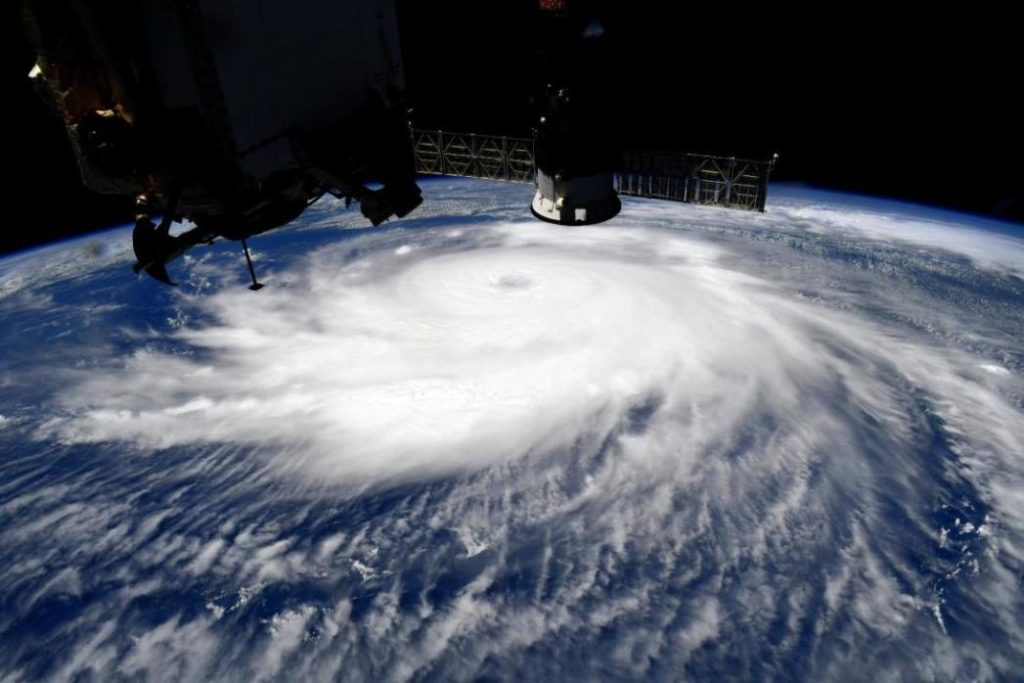

Hurricane Laura as seen from the International Space Station as it intensified. IMAGE: Chris Cassidy/NASA

As forecasters watched a tropical storm struggle to develop in the Caribbean earlier this week, they were pretty sure it might develop into something worse.

But they just couldn’t tell how bad.

After keeping forecasters guessing for several days, Laura suddenly strengthened right before landfall, reaching Category 4 with sustained wind speeds of 150 mph as it crashed into the Louisiana and Texas coastlines with damaging winds, widespread flooding and a destructive storm surge.

Laura’s dramatic transformation was the latest occurrence in a worrying trend of what weather forecasters call “rapid intensification” of major storms, a phenomenon that is being linked to global climate change and warmer seas.

What was once a rare occurrence, is now becoming more common. Just in the last two years scientists have witnessed several in quick succession, including Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and Michael in 2018.

“Rapidly intensifying storms like Hurricanes Laura, Michael, and Harvey are dangerous because they can catch forecasters and the public off guard,” warned Jeff Masters, a hurricane scientist and contributor to Yale Climate Connections published by Yale University’s School of the Environment.

Hurricane Laura increased in strength by 65 mph in just 24 hours on August 26. That ties Hurricane Karl of 2010 for fastest intensification rate in the Gulf of Mexico on record, according to Masters.

Historical records show that since 1950, the eight storms have intensified by at least 40 mph in the 24 hours before landfall. Three of those storms, below in bold face, occurred in the past four years: Laura, Michael and Harvey.

“It’s the forecaster’s nightmare. You go to bed with a tropical storm and wake up with a Cat 4,” said Kerry Emanuel, a hurricane scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Laura was not quite the worst scenario as it struck a relatively unpopulated region of the coast and there was enough time to evacuate residents by bus before the winds arrived. “We lucked out,” says Emanuel.

To be fair to the forecasters, it’s unfair to expect absolute accuracy, said Emanuel, who is working on a project to incorporate more probability modeling for wind strengths to help homeowners make evacuation decisions.

“No matter how you perfect your models you can’t predict beyond some time horizon. Even if you measure every molecule in the atmosphere you still won’t get there,” he said.

“Like a bomb going off”

Bob Bunting, an atmospheric scientist and founder of the Climate Adaptation and Mitigation Center, says the term ‘rapid intensification’ “doesn’t really capture what’s going on.” He prefers to call it “explosive development,” describing it as “like a bomb going off.”

The transformation is visible on satellite images that show the storms developing the tightly wound spiral that are the signature of hurricanes. “They also have very small eyes, often barely 10 to 20 miles wide,” he added. He likens it to an Olympic ice skater doing a spin and pulling their arms in to spin faster. “The same amount of energy is being concentrated in a smaller and smaller area. A hurricane is the same. As it spins faster it shrinks the eye down,” he said.

The main contributing factor is warmer water which scientists say is where storms get their energy. “That water is like rocket fuel for hurricanes,” said Bunting.

Due to climate change caused by greenhouse gases trapped in the upper atmosphere, scientists say more and more of the sun’s energy is being absorbed in the oceans. About 93% of that excess energy is stored in the oceans, said Robert Corell, an oceanographer and former assistant director for Geosciences at the National Science Foundation.

“Most of that is on the surface and a few hundred meters below,” he said. “Systematically, these bigger water masses are getting warmer and warmer. We can measure that,” he added.

When a storm passes over the warmer water in the summer, evaporation causes moisture in the air, allowing the heat energy to be transferred from the sea into the air, and sucked into the storm winds.

Bunting compares it to watching boiling water on a stove and the heat generated as it transforms into water vapor. “When a hurricane passes over water like that, the ocean releases the stored energy back into the atmosphere. It’s basic physics, the transfer of heat from one form of energy to another. It goes from potential energy into kinetic energy,” he said.

Current temperatures on the Gulf of Mexico are between one and two degrees above average for this time of year, or about 30-31 degrees C, according to the NHC. “That’s a lot. That’s really warm,” said Mark DeMaria, Chief of Technology and Science at the National Hurricane Center.

But, the environmental conditions affecting Laura this week created more than usual uncertainty, according to It was initially predicted to pass over Hispaniola and the length of Cuba, which was expected to weaken it.

However, it ended up tracking farther south over open sea, allowing it to maintain its strength. “We knew we had the right conditions for development, the Gulf was warmer than usual average and the upper atmosphere was pretty conducive,” he told Univision. But the storm took time to organize as it moved past Cuba into the Gulf. “It didn’t intensify right away,” he said.

That’s why forecasters were cautious, wondering if and when it would develop as it made its way northwards. The NHC settled on a forecast that it would reach a Category 3 storm with wind speeds of over 110 mph, before suddenly having the revise that upwards as it neared the coast, making landfall as the strongest hurricane in Louisiana history, and the fifth-strongest hurricane on record on the U.S. mainland.

New tools

The good news, DeMaria says, is that thanks to some sophisticated new tools in its arsenal, the hurricane center’s ability to detect the conditions for rapid intensification is improving. Just in the last five years accuracy has improved thanks to a mixture of technologies, including a super-computer able to crunch mathematical data and new infrared satellite imagery that can measure the sea surface temperature.

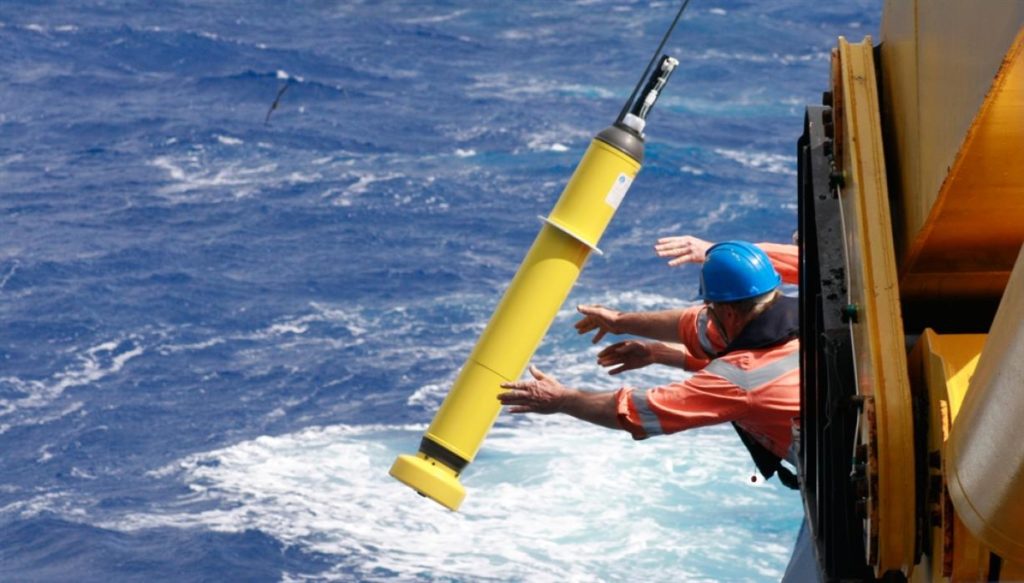

Robotic instruments dropped into the ocean, known as ‘Argo floats’ can drift with the ocean currents and dive under water to a couple of hundred meters to take measurements. That’s important because, especially in the Gulf of Mexico the depth of warm water can vary enormously.

The Argo float measures temperature and salinity in the ocean. It can dive about 1.2 miles deep and then surfaces to transmit data in real-time via satellite. IMAGE: NOAA

Experimental, unmanned semi-submersible ‘ocean gliders’ are being deployed to explore the water in the path of storms to get a better data readings on conditions.

“A lot of things have come together,” he said. But much remains to be known about the inner core of hurricanes and understanding how they develop. “We’re still not very good it,” DeMaria confessed.