Fossil Fuels — at the Top of the COP26 Agenda

In the previous installments of this three-part article we discuss the International Energy Agency report “Net Zero by 2050” and the related results of the June G7 Summit meeting. In this final installment, we take a look at the impact of net zero policies on the use of fossil fuels — likely to be a headline issue at COP26 in November.

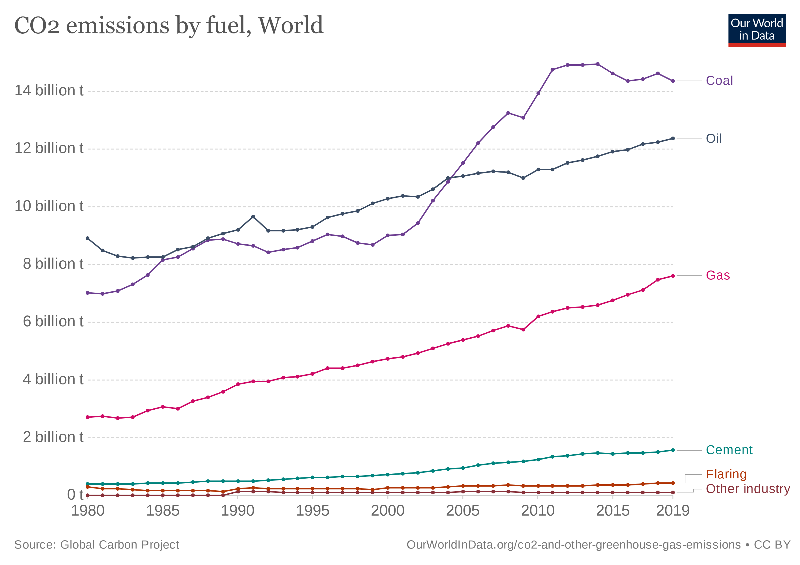

Fossil fuels (coal, oil and gas) play the lead role in global energy systems. As we know, the combustion of fossil fuels and the accompanying release of carbon dioxide is the primary driver of global climate warming. Particulate matter from fossil fuel emissions is estimated to account for nearly one in five deaths worldwide.

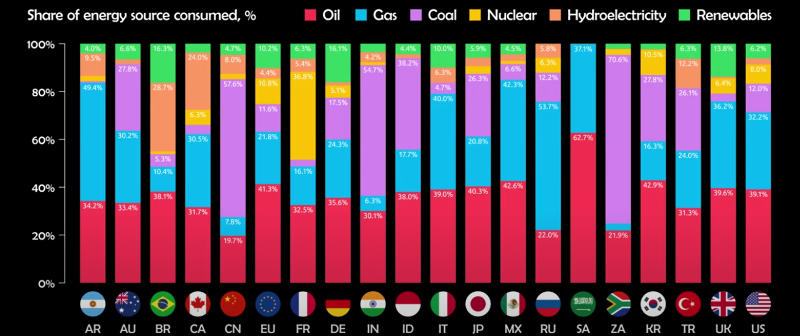

Nonetheless, as we can see in the following chart, the twenty largest economies in the world remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels to meet their energy needs.

Source: Visual Capitalist

The key element of the IEA Net Zero 2050 roadmap is a rapid reduction in fossil fuel consumption, starting with an immediate halt to the construction of unabated coal-fired power plants; no new oil and gas fields approved for development; and no new coal mines or mine extensions.

Big Business

These changes are easier said than done — fossil fuels are also big business. Fossil fuel companies have a combined market capitalization of $18 trillion, a quarter of the total value of global equity markets. They account for $8 trillion of corporate bonds, over half the non-financial corporate bond market. Unlisted debt (mostly owed to banks) is in the neighborhood of $30 trillion. A 2018 World Bank estimate projects future profits from fossil fuels at $39 trillion. A recent study by U.K. think tank Carbon Tracker estimates that companies expecting to continue for some time with business as usual could project profits in excess of $100 trillion.

Governments also have a vested interest in the fossil fuel industry, in the form of subsidies. A 2021 report by BloombergNEF finds that the G20 countries provided government support to the tune of $3.3 trillion between 2015 and 2019. The report notes: “At today’s prices, that sum could fund 4,232 GigaWatts in new solar power plants – over 3.5 times the size of the current U.S. electricity grid.”

Governments get the Message

Together the fossil fuel industry and its supporting government policies are like the cumbersome supertankers and bulk carriers that carry oil and coal — they can’t change direction very quickly.

However, after 40 years of ever deeper, ever more compelling scientific research, and steadily increasing public concern, governments have got the message — climate warming is real, it’s a threat to society, our injection of CO2 into the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels is the proximate cause, and our citizens expect us to do something about it.

In the U.S., President Biden was elected on a platform that committed to address climate warming, starting with rejoining the Paris Agreement after a four year hiatus. European countries are individually and collectively far ahead of the U.S., committing to both a rapid wholesale switch to electric vehicles and a robust emissions trading system, among a host of other initiatives.

As we head into the November Conference of the Parties to the Paris Agreement (COP26), first the G7 and then the G20 nations have publicly elevated their commitments to diminish our output of CO2 to the point where we can attain Net Zero output by 2050. This will give us a 50/50 chance of limiting climate warming to 1.5ºC, and very good odds of keeping warming below 2ºC.

This is all well and good, but that supertanker is still plowing ahead. The fossil fuel industry says it got the message but its actions have been looking pretty much like business as usual. We’ll take a look at recent developments in the oil industry, then coal.

The Oil Industry had a Very Bad Week

In one week in May, fossil fuel business as usual went out the window.

First, a court in the Netherlands came down with a landmark ruling against Royal Dutch Shell, ordering the company to cut greenhouse gas emissions 45% by 2030 from 2019 levels. Its existing carbon management strategy was deemed “not concrete.” In addition, the court ruled that Shell is also responsible for emissions from customers using its product, and from its upstream supply chain — so-called Scope 3 emissions. This includes emissions from end-user combustion of oil and natural gas.

First, a court in the Netherlands came down with a landmark ruling against Royal Dutch Shell, ordering the company to cut greenhouse gas emissions 45% by 2030 from 2019 levels. Its existing carbon management strategy was deemed “not concrete.” In addition, the court ruled that Shell is also responsible for emissions from customers using its product, and from its upstream supply chain — so-called Scope 3 emissions. This includes emissions from end-user combustion of oil and natural gas.

As you might expect, Shell has appealed the ruling, so this isn’t over yet. Similar court cases in the U.S. have failed repeatedly, with the courts punting the issue to the legislative and executive branches of government.

On the same day as the Shell decision, at a shareholder meeting for oil giant Chevron, investors voted to require the company to reduce its contribution to climate change by adding Scope 3 emissions to its existing Scope 1 and 2 emissions reduction plan. In Chevron’s case, Scope 3 emissions made up a whopping 91% of its emissions from all products sold in 2019.

Analysis shows that the only way for Chevron to reduce Scope 3 emissions is by reducing production, either internally or through divestment. (It seems reasonable to expect that the same would be true for other oil and gas companies.)

Chevron’s day could have been even worse — a shareholder proposal requiring a report on the effect of the IEA Net Zero 2050 plan and its reduction in fossil fuel demand on Chevron’s financial position and business strategy was nearly successful, gathering 48% of the vote.

The big event of the week was reserved for Exxon Mobil. The company experienced a full-blown revolt by shareholders unhappy with the company’s climate change response and its mediocre financial performance. The shareholders successfully ousted three board members and replaced them with experts in renewable energy and climate science, a stunning defeat for Exxon senior management.

Their victory came after a six-month campaign led by a small hedge fund quixotically named Engine No. 1. It was joined by three of the biggest U.S. pension funds — two from California and one from New York state — and the three largest asset managers, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street. Together the three asset managers total $19 trillion under management and hold 18.5% of Exxon’s stock and 19.4% of Chevron’s.

Markets are Forcing Change

Considering the Shell, Chevron and Exxon events, Prof. Paul Griffin (University of California, Davis) suggests that the push for change in the fossil fuel industry will come from market forces, not governments or courts. Fossil fuel investments have dramatically underperformed compared to the overall market, losing roughly 20% of their value in the last decade, during the strongest bull market in 50 years. Faced with that situation, large investors either reduce their holdings or use their votes to change corporate strategy. It appears that Exxon’s largest shareholders think that their investments will enjoy higher returns if the company pivots from a high risk, carbon intensive path and gets on board with the energy transition to clean energy products and services.

Visible activism by the large asset managers is part of the trend to ESG-based investment — requiring corporate commitment to environment, social and governance policies. Exchange-traded funds focused on ESG pulled in an eye-popping $112.5B in the 12 months ending in May, according to Bloomberg. On July 27, two asset managers alone closed on $12.4B in climate investment funds. At the same time, worldwide investment in climate technology companies is skyrocketing, exceeding $14B in the first half of 2021.

Governments can be a powerful influence through their public investments — Sovereign Wealth Funds and public pension funds in particular. By incorporating ESG factors and climate objectives into their investment strategies, governments can shift public investments away from fossil fuels. For example, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund, with assets of $1.1T, was specifically set up to invest government revenues from fossil fuel industries into more sustainable sectors.

Encouraging trends can also be seen in the bond market. By December 2020, the Climate Bonds Initiative database of Green Bonds (bonds with 100% of net proceeds dedicated to green assets) exceeded $1T. The U.S. is the largest source of green debt, with a total greater than $52B.

Under the Biden administration, ESG investment is drawing increased attention from the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Despite heavy lobbying by the fossil fuel industry, SEC chair Gary Gensler said recently that the agency intends to develop a mandatory climate-disclosure rule by the end of the year. The SEC may also go as far as requiring climate disclosures in a company’s annual 10K report. Gensler says the SEC is considering requiring Scope 3 emissions disclosure — a measure vehemently opposed by the American Petroleum Institute, the oil and gas industry’s leading lobby group.

At the same time, the G20 nations have announced their unified support for global implementation of a process for climate risk disclosure, following the TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures) framework.

By illuminating climate-related risks and their financial implications, these regulatory developments are likely to further direct investment away from fossil fuels and toward lower risk climate-friendly opportunities.

Coal — Not Dead Yet

Coal is the most emissions-intensive of the fossil fuels, accounting for 40% of global CO2 emissions. Electricity generation by coal-fired power plants alone accounts for 30% of global emissions. Given that wind and solar power are cheaper sources of new power generation in most countries, coal has become a logical focal point for efforts to rein in climate warming. Recall that the IEA roadmap to reach net zero emissions in 2050 requires “no investment in new fossil fuel supply projects, and no further final investment decisions for new unabated coal plants” going forward. Considering that the principal market for coal is electricity generation, this would seem to suggest that industries involved in coal mining and coal-fired powerplant construction are not long for this world.

Not so fast.

Many developing countries, notably India and China, rely on coal fired power plants for much of the generating capacity needed to meet their rapidly growing electricity demand. There is currently about 2,000 GW of coal-fired power generation capacity worldwide, over half of it in China. On top of that, the G20 countries have almost 400 GW of new coal-fired power plants in the pipeline, also led by China with 250 GW of capacity planned or under development.

More power plants mean more coal, and the world’s coal producers are currently planning as many as 432 new mine projects, capable of producing 2.28 billion tonnes per year. China, Australia, India and Russia together account for three quarters of the new mining capacity.

Coal Mine, Indonesia

Given these developments, it comes as no surprise that the July 2021 G20 meeting of climate and energy ministers failed to reach a consensus on phasing out coal. China, Russia, India, Turkey, Indonesia and Saudi Arabia were among those supporting coal. Even Japan’s energy plan shows the country still generating 19% of its electricity from coal in 2030.

The final position of the G20 will be determined when the heads of state meet in Rome, a month before the COP26 meeting in Glasgow. Some of the resistance displayed at the ministerial meeting to the well-publicized U.K. objective for COP26 “to consign coal to history” could well be intended to create some negotiating room for the Rome meeting.

Coal mines have a lifetime of 20 to 30 years and a global marketplace shifting to a low carbon economy puts the new mining projects at risk of up to $91 B in stranded assets. A 2021 study by Imperial College London projects that a third of today’s coal mines risk becoming stranded assets by 2040 if we implement a sustainable development scenario sufficient to keep climate warming below 2ºC.

Similar financial risks accompany the global fleet of coal-fired power plants. The global average coal plant lifetime is 38 years. With the average age of coal plants in Asia only 12 years, they have decades of economic life and CO2 emissions remaining. Nonetheless, China’s President Xi says China will reach net zero by 2060, although his plan doesn’t begin to phase out coal until 2026.

A Global Energy Monitor report estimates that based on the IPCC SR1.5 pathway to “well below 2ºC”, China’s coal power capacity needs to drop to 1,000 GW by 2026, and to 600 GW by 2030. If we assume that coal plants around the world are retired when reaching a common age limit, then the well below 2ºC pathway requires coal plants to be retired at 21 years. On the 1.5ºC pathway, coal plants would have to retire at just 17 years. Either way, the potential early retirement of multibillion dollar facilities is not welcome news for investors.

Understandably, the fossil fuel industry is hoping to find technology solutions that could mediate emissions and extend the allowable lifetime of their costly investments…

What About Carbon Capture and Storage?

Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage (CCUS) is promoted as the technology that would allow us to keep burning coal, crude oil and natural gas while achieving our climate goals. But how realistic is this?

Carbon capture and storage technology has been operational for decades. The first carbon capture and storage project was brought online by Shell in 1972. Initially carbon capture was used to remove CO2 from raw natural gas, and the CO2 was simply vented to the air. The Storage component of CCUS is usually accomplished by pressurizing the extracted CO2 and transporting it by pipeline to an underground storage site. “Utilization” most commonly takes the form of injecting the pressurized CO2 into an oil field to boost output, a process called Enhanced Oil Recovery, or EOR.

Current CO2 capture technology is at best 85-90% efficient. However, in practice the net performance is much lower. A 2019 study found that, on average, a carbon capture installation at a representative coal plant was only 55.4% efficient.

CCUS may not be perfect, but concern about climate warming has renewed interest in the technology by all elements of the fossil fuel industry. Let’s look at coal first.

As we discussed earlier, coal is a problem because of its widespread use in electricity generation, particularly in China and the developing nations in the rest of Asia. This year, for the first time, China has included CCUS in its newest five year plan in support of its emissions reduction goals for coal-fired power generation and hydrogen production. Given the size of its coal-fired power plant fleet, CCUS deployment at an unprecedented scale will be required to meet its net zero goal.

On a smaller scale but no less ambitious, Indonesia’s updated Nationally Determined Contribution to the Paris Agreement relies on CCUS fitted to 76% of its “zero-emissions” coal-fired power plants as part of a net zero 2060 pathway.

Relying on CCUS to meet climate goals is a major gamble. The performance, economics and scalability of these technologies is uncertain at best. A 2015 IPCC Special Report on carbon capture estimates that adding carbon capture to a coal-fired power plant increases the capital cost of a new plant by an average of 63% and increases the cost of produced electricity by 57%. Retrofitting existing plants is even more costly. The cost to build a typical 1 GW coal-fired power plant without carbon capture is roughly $1.3B. Adding carbon capture raises the cost to $2.1B. All of these cost estimates exclude the added cost of carbon transport (typically by pipeline) and storage, not to mention potential liability risks associated with CO2 leakage.

So, given the low cost of electricity generation from renewables, adding the extra cost of CCUS to coal-powered generation doesn’t seem like a winning proposition from a climate perspective. Political considerations — energy security, in the case of China and Indonesia — are really what’s keeping the coal fleet afloat for the time being.

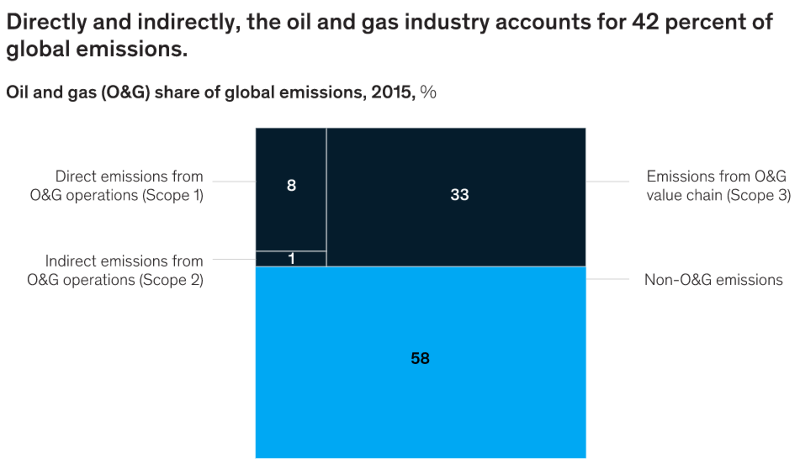

But “Big Oil” (think Chevron and ExxonMobil) is also trumpeting CCUS as it’s path to lower emissions. How realistic is that? The key thing to keep in mind is explained by the following chart from a recent McKinsey & Company report:

Source: McKinsey & Company

When Exxon or Chevron talk about “going carbon neutral” they area referring to the Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions — the direct and indirect emissions from company operations, from drilling through transport of crude oil or natural gas to refining the final product. This is not trivial. As the chart above shows, these activities account for a total of 9% of global emissions. Using CCUS to reduce those emissions is undeniably a good thing. However, the elephant in the room is the Scope 3 emissions — the result of using gasoline to power your car, for example — which account for no less than 33% of total global emissions. Recall the Shell court case we discussed earlier. The court’s decision implies that it is a bit disingenuous for a company to clean up its internal operations and declare “job done” while disavowing responsibility for the societal impact of its products.

The IEA Net Zero 2050 report and the Princeton University “Net Zero America” study show that a successful 2050 climate strategy requires reducing our use of fossil fuel products to the greatest extent possible, as quickly as possible, and only then using technologies like CCUS to help deal with the remaining emissions.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Governments around the world are promoting ever more ambitious climate measures. Encouraging examples abound. The EU is implementing the world’s strongest emissions trading system and it’s implementing a rapid transition to electric vehicles. In the U.S. the Biden administration is proposing to phase out fossil fueled power. There are many more.

And yet… Writing in Politico, Michael Grunwald reminds us of an unpleasant fact: “Future warming is literally baked in.” By which he means that the emissions we are putting in today will inevitably result in additional warming beyond the 1.2ºC we have already surpassed. We can start to flatten the curve, but temperatures will still rise.

My guess is that limiting climate warming to 1.5ºC is already out of reach and it will require extraordinary efforts just to keep climate warming below 2ºC. As Grunwald reminds us, “…we still have 4 billion megawatts of fossil-fueled electricity and 1 billion fossil-fueled vehicles that will keep warming the planet until they’re replaced.” Nonetheless, we are making progress, and every tenth of a degree of warming we can prevent the better our future will be.

As we approach the G20 Summit in Rome, and the COP26 conference in Glasgow, let’s use our newfound knowledge of the fossil fuels situation to applaud some encouraging recent developments.

Less that a week ago at this writing, a new initiative was launched with the aim of accelerating the closure of Asia’s coal-fired power plants. According to Reuters, a consortium of financial firms. let by UK insurer Prudential, and including the Asian Development Bank, lenders HSBC and Citi and BlackRock Real Assets plans to create public-private partnerships to buy out power plants and shut them down within 15 years — well ahead of their expected lifetime. The proposed Energy Transition Mechanism involves two financial assistance programs: a carbon reduction facility that would buy and operate the power plant, and a renewables incentive facility to kickstart investment in renewables and storage to eventually replace the output of the coal plant. The carbon reduction facility would take advantage of a lower cost of capital than would be available to a commercial enterprise, allowing the plant to run at a higher margin over the reduced lifetime to generate the same returns. The cash flow would repay debt and investors. Prudential’s estimates show that it would be possible to retire 50% of a country’s coal plant capacity at a cost of $1M to $1.8M per megawatt — roughly $9-$17 billion for Vietnam, for example.

At a meeting in early July, IEA Executive Director Fatih Birol and the United Arab Emirates’ Special Envoy for Climate Change agreed to work together to facilitate a clean energy transition as the UAE economy shifts away from a heavy reliance on fossil fuels. A similar meeting will be hosted by the Sultanate of Oman and the IEA in October, attended by ministers from across the Middle East and North Africa. The region is well-positioned for the transition, with some of the world’s best solar resources and the financial resources to pivot quickly to clean energy technologies.

Also in July, the government of Greenland announced that it will cease all oil exploration going forward, both on land and offshore. A government statement declared “The future does not lie in oil. The future belongs to renewable energy…” Estimates place Greenland’s oil and gas reserves at over 50 billion barrels.

Finally, climate finance will be front and center at COP26 in November, under the able direction of the UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, Mark Carney. The former Governor of the Bank of England is also the Prime Minister’s Finance Adviser for COP26. In that capacity, he will lead the COP26 Private Finance Hub, which has the objective to “ensure that every professional financial decision takes climate change into account.” One of the Finance Hub goals is to implement a common framework for improving corporate climate disclosures, based on the recommendations of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). To enable investors to understand how their portfolios are aligned with the net zero transition, firms will have to report current and projected emissions in a portfolio and their contribution to climate warming. No more smoke and mirrors!

Another powerful financial group relying upon TCFD disclosure recommendations is the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative. Its 128-plus members cover more than a third of all assets under management globally, totalling $43 trillion. Members commit to reach net-zero financed emissions across all assets under management by 2050 or sooner, with measurable near term science-based targets for 2030 or earlier. Targets are to be met with direct emissions reductions wherever possible — offsets are a last resort. Members include Allianz Global Investors, Vanguard Group, AXA, Fidelity, HSBC, Lazard, UBS, State Street and BlackRock.

Why are these finance-related items important? Shouldn’t we focus on climate warming science and government policy initiatives? The latter are certainly important, and both are well-covered here and elsewhere. But “money makes the world go ’round,” and in 2020 big-name banks and investors provided $750B of financing for fossil fuel companies. Big names? How about JPMorgan Chase ($51B) or Bank of America ($42B). Going forward, financial disclosures linked to verifiable emissions goals will be the key to functional regulatory policies in support of global and national economies’ transition to a net zero world.